With the increasing pressure from western sanctions, fears have amplified over the risk of sabotage, espionage and other hybrid actions from Russia targeting western critical infrastructure, including that of underwater infrastructure, LNG terminals and supply lines.

Europe’s network of pipelines, power cables and gas terminals play a vital role in supporting the UK’s energy sector. Although the UK is no longer part of the European Union, its energy system remains closely tied to the continental infrastructure. Among the UK’s European partners, Norway stands out as a particularly important partner and supplier.

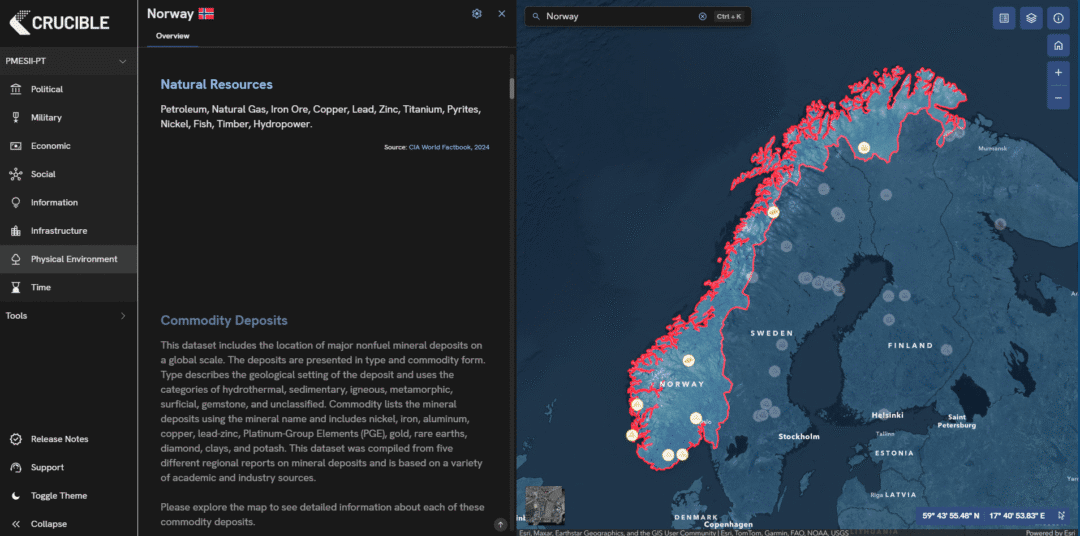

Norway is now Europe’s main source of natural gas, after Russia, since the start of the conflict in Ukraine. Norwegian exports have become critical to the region’s energy stability. Around one third of the UK’s gas imports come from Norway through the Langeled pipeline. The UK has some of the lowest levels of gas storage in Europe, making it vulnerable to short-term supply shocks and high demand periods.

Figure 1: Screenshot of Roke’s Platform Crucible, showing Norway’s natural resources.

NATO and EU policy makers have highlighted ongoing concerns over the resilience of European critical infrastructure. One major concern is that a significant portion of critical infrastructure is privately owned. While security is becoming a major motivation for investment; shareholders have prioritised efficiency, creating interconnected systems where one failure can cascade into crisis.

One prominent example of how these supply disruptions can have a knock-on effect is the 2022 Nord Stream explosion which caused an immediate impact on the supply of natural gas from Russia into Europe. This caused a dramatic spike in European gas prices, which had the potential to trigger an economic slump and lead to recession.

Figure 2: Image of the Nord-stream incident captured by the Swedish Coast Guard

This issue is not limited to gas supplies; underwater cables are also a crucial infrastructure that support the global economy, defence and communication systems. Modern subsea cables have the capacity to carry hundreds of terabits per second, surpassing the capacity of satellites. When issues occur with these cables, the origin of this disruption can be difficult to detect, easily denied and have dramatic consequences.

Since the start of the Ukrainian conflict, GPS and GNSS manipulation has increased in countries surrounding Russia and in areas such as the Baltic Sea. Such interference increases the difficulty to accurately track or identify ships in affected areas, complicating efforts to determine presence of vessels when suspicious damage occurs.

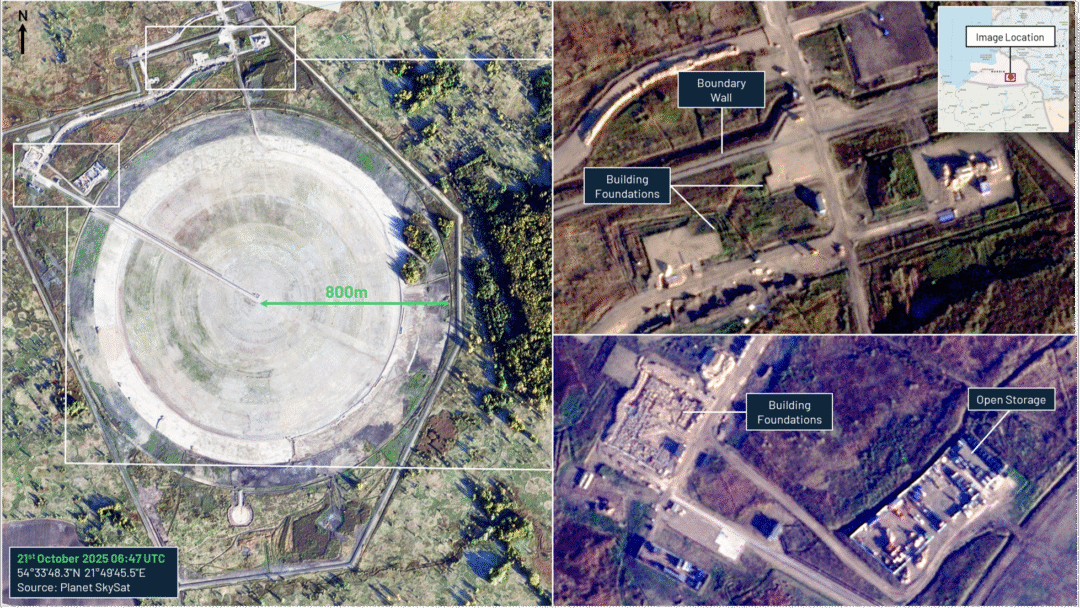

Russia has long invested in advanced Electronic Warfare (EW) capabilities, which include the ability to jam and manipulate satellite navigation signals, with the aim to disrupt situational awareness. These capabilities have continued to develop throughout the Ukraine conflict and include the construction of a Circularly Disposed Antenna Array (CDAA) within Kaliningrad. This military-grade antenna array is designed for radio intelligence and has a long-range capability. This could not only monitor communications in Ukraine and NATO countries but has the potential to disrupt satellite navigation systems used by drones, airplanes and ships.

Figure 3: Annotated Planet Sky-Sat imagery of the Circularly Disposed Antenna Array (CDAA) within Kaliningrad.

This capability along with the growing pattern of Russian activity, ranging from GPS manipulation and drone incursions across Europe to disinformation campaigns on social media, highlight the breadth of hybrid warfare tactics. This hybrid campaign likely aims to undermine trust in NATO, obscure accountability and test the resolve of NATO countries.

The integration of civilian and military systems in defence and security, results in commercial companies being also present within this hybrid threat environment. With this convergence, the demand for stronger collaboration of defence industries and governments to protect critical research and supply chains is critical.

If you think Crucible could support your organisations operations, get in touch with us now to find out more or run a trial.