After Russian drones entered Polish airspace between the 9th and 10th September, shortly after, Russia began the joint strategic exercise Zapad 2025.

Due to Russia’s commitment in Ukraine, fewer Russian troops were involved, but the exercise included military contingents from Belarus, Burkina Faso, India, Iran, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), and Mali. It highlighted the Russian-Belarusian capability to conduct large-scale, multi-domain operations, including that of potential nuclear deployments.

The exercise occurred over multiple locations and domains including the Arctic and incorporated scenarios of a large-scale aggression by western countries towards Russia. The inclusion of these multiple domains and varied scenarios, such as the Russian Northern Fleet conducting a tactical landing of naval troops on the unprepared coast of Alexandra Island in the Arctic Ocean, likely serves as a demonstration of Russia’s intent to assert control over the High North.

Figure 1: Image of Russian troops and equipment, during ZAPAD 2025, conducting a tactical landing on Alexandra Island in the Arctic Ocean. Source: thebarentsobserver.com

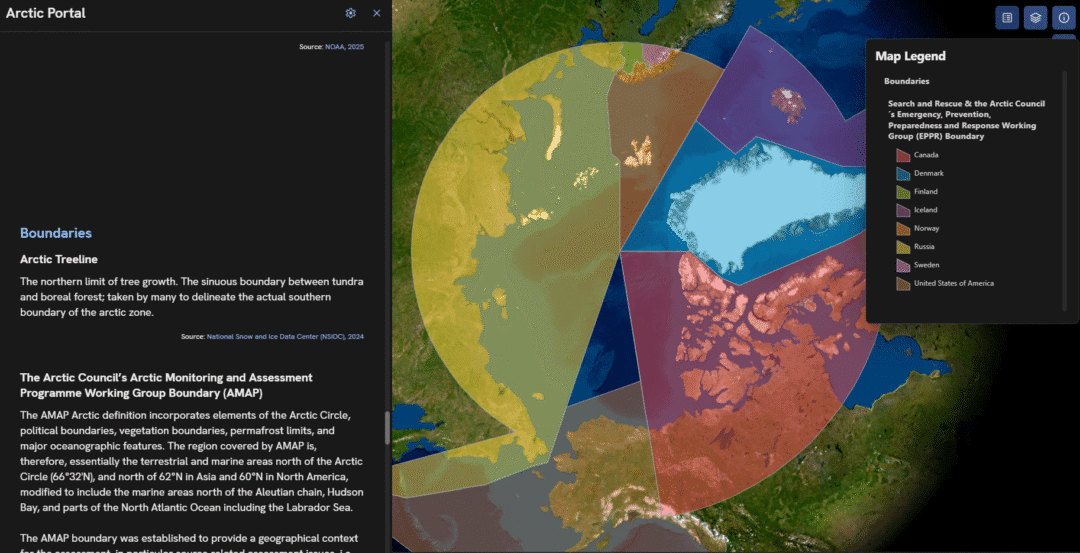

Since the end of the Cold War, the eight Arctic states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden and the United States) have collaborated on issues such as sustainable development, environmental protection, and scientific research, maintaining a shared commitment to peace and stability.

Figure 2: Screenshot of Roke’s Platform Crucible, displaying the Arctic Portal tool and visualising Arctic Ocean country boundaries.

This cooperation has largely been facilitated through intergovernmental forums like the Arctic Council. However, this collaboration has been increasingly under friction as the region gains greater strategic importance for major global powers and following Russia’s suspension due to the Ukraine conflict. This rise of Arctic significance, driven by the effects of climate change, has the potential to open trade routes and access to natural resources such as oil and gas and critical minerals such as platinum, palladium and nickel. These critical minerals have a wide array of military uses. With recent decisions to increase NATO defence spending, this will likely translate into a higher demand for critical minerals including platinum group metals (PGMs) which include Platinum and Palladium.

Due to major geopolitical changes, new strategic approaches have been developing throughout 2025, changing the high north from a region of cooperation into a venue of strategic competition. This can be seen in recent actions by the US with a renewed interest in Greenland, the signing of memorandum to authorise the purchase of icebreaking ships from Finland and executive orders with aims to maximise the development of Alaska’s natural resources.

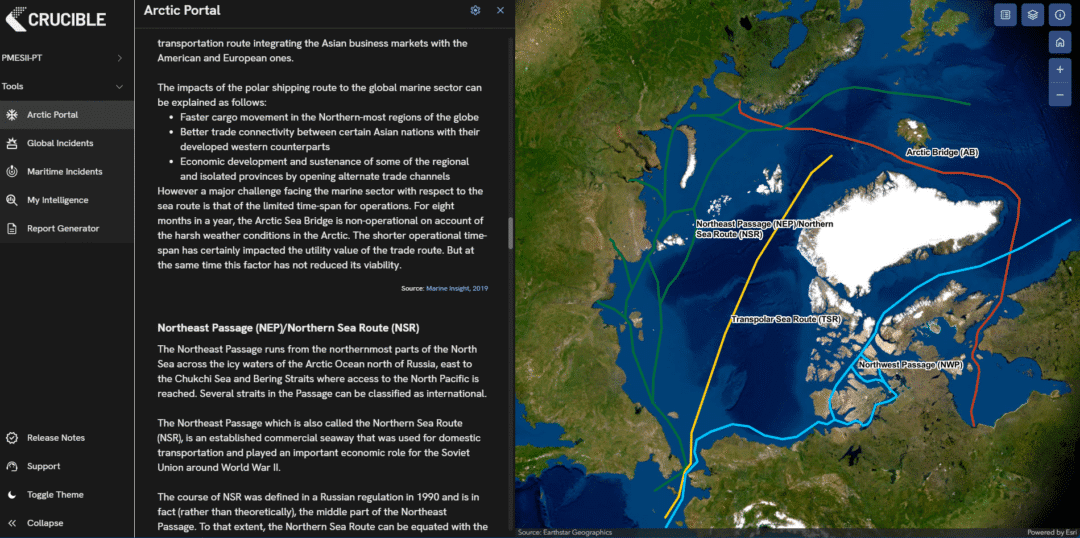

In comparison, China, who has declared itself as a near-arctic state, has increased cooperation with Russia in the opening of future maritime trade routes focusing initially on the Northern Sea Route (NSR).

Figure 3: Screenshot of Roke’s Platform Crucible, displaying the Arctic Portal tool and displaying shipping routes.

Russia’s Arctic trade is heavily reliant on its close partnership with China, the primary destination for shipments along the NSR. In 2024, an estimated 95% of east-to-west cargo transits across the NSR were exports from Russia to China.

This trade flow not only highlights the strategic importance of Sino-Russian relations in Arctic logistics but also represents a significant economic lifeline for Russia. The NSR enables Russia to monetise its vast natural resources (particularly oil, gas, and minerals) by reducing shipping times to Asian markets. As Western sanctions continue to restrict Russia’s access to European trade, the NSR-China corridor has become a critical revenue stream, helping to stabilise Russia’s export economy and support infrastructure investment in its northern regions.

If you think Crucible could support your organisations operations, get in touch with us now to find out more or run a trial.